Last week we thought a little about some differences in English Bible translations. All English translations would presume to take God’s Word literally and are trying to best convey what God is saying to His people through the written word. A word-for-word translation attempts to convey God’s message directly as recorded in the original language which often makes it more difficult for an English reader to understand what is being said. Whereas a thought-for-thought translation attempts to convey God’s message in terms of the thrust of the thought which makes it easier to understand but can sacrifice preciseness of the text. So how can we be sure that what we are reading in our Bible is actually the Word of God as it was originally given? To answer this, let’s step back in time and see how the Bible (we’ll focus on the New Testament) has been handed down throughout the ages. During the time of the New Testament and shortly thereafter, there were a number of different methods for recording Scripture. The books of the New Testament were primarily written on pieces of papyrus (a paper like material made from a papyrus plant) and passed throughout the churches. If a new copy was needed it had to be copied by hand which took time and careful attention to detail. There were a number of methods to check the accuracy of their copy and given the sheer volume of the work, there are a surprisingly few differences between copies. When looking at the manuscripts of the New Testament and their copies, there are four general categories that differences (variants) of text are classified. 1. Spelling errors or nonsense errors- The scribe could simply misspell a word, perhaps adding or forgetting a letter in the word, creating a different word entirely. After copying line after line of text in a dimly lit room, the scribe’s eye could ‘wander’ and lose his place whereby he might start copying on a different line of text. 2. Minor changes that do not alter meaning- This category is primarily for cases where word order is switched around between copies which can happen in Greek without affecting the meaning of the sentence. 3. Changes that are not plausible- Sometimes a well-meaning scribe would add a word or two to try to clear up a difficult reading or try to make it sound like another part of Scripture. Other times a scribe with a certain theological agenda might make an intentional change. For instance, Matthew 27:35 reads: Then they crucified Him, and divided His garments, casting lots.” Whereas a variant reading has: Then they crucified Him, and divided His garments, casting lots, that it might be fulfilled which was spoken by the prophet: “They divided My garments among them, And for My clothing they cast lots.” This is reading is rejected because it adds a line of explanation to the text that isn’t necessary which likely reflects a scribe trying to clarify the text. 4. Major changes that are possible- Out of all the variants of text, these major changes account for less than 1%. Two of the most obvious major variants are Mark 16:9-20 and John 7:53-8:11 which were omitted in the earliest manuscripts and do not seem to fit the writing styles of Mark or John. A few things must be said in light of this information. While we have no original copies of the New Testament (there are portions of manuscripts which date to within 100 years of the completion of the New Testament) there is remarkable continuity between all available copies. If an error was discovered, that copy was destroyed. While there are a number of different possible readings of texts there is broad consensus of what comprises the Majority Text (the accepted text and likely the original text). Reading all this may have caused you to wonder about the accuracy of your Bible and whether the words you have are the words God intended to be there. This information can be unsettling but it must be said that the disputed texts of Scripture do not change the meaning of Scripture or any theology derived from it. We can have confidence in the Greek text as we have it today (from which our English Bibles are translated) as it was meticulously maintained and preserved and accurately reflects the original text of God’s Holy Word.

1 Comment

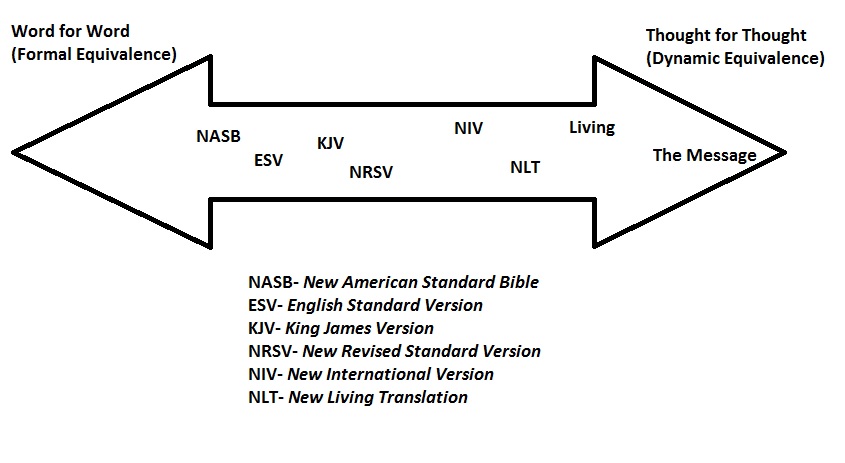

I often have people ask me which translation of the Bible is the best to use. My reply is, “It depends on what you are doing with it.” This sometimes catches people off guard assuming that there should be a one size fits all answer, after all how can the Bible be God’s unchanging Word if every translation seems to say something different? One of the first things to keep in mind about our English Bibles is that they are a translation from the original languages of Hebrew and Greek. As in all translation work, choices of sentence structure and word order must be made. We often structure our sentences in English around the basic layout of Subject, Verb, Object upon which we add adjectives, adverbs, or other modifiers. Other languages do not always structure their sentences in such a way, which makes word for word translating very difficult. For instance, our English Bibles have Jesus saying in John 15:1, “I am the true vine, and My Father is the vinedresser/gardener.” The word for word translation in the Greek is, “I am the vine true, and the Father of me the husbandman is.” A precise word for word translation does not make sense in the way we structure English. While this particular example is relatively straightforward (you can easily move the pieces around so they make sense to us) not all sentences in the Scriptures are. There are sometimes difficult decisions which must be made about which words belong together. In the above example, one can also see that not every Greek or Hebrew word has an English parallel. This is the real challenge of translation. Each translation or version of our English Bibles has a team (you can find out who was involved in the translation work by flipping to the front pages) working together to bring the Hebrew or Greek language into English. It is their task to choose a word which is true to the original language but also gives understanding for modern readers. The Greek word in John 15:1 ‘husbandman’ therefore gets translated into English as vinedresser or gardener depending on your translation. There are other instances in Scripture where more than two options of word choice could plausibly be used. These are two very basic issues which makes translating Scripture from the Hebrew or Greek to English challenging (there are many other issues which I’d be happy to talk with you about). We end up with a variety of translations because each version tries to do something different. This results in a spectrum of translation. Some versions try to be as true to a word to word translation as possible often at the expense of readability. This is known as Formal Equivalence. On the other extreme there are versions which strive for easy of reading and understanding (capturing the thought of the sentence) at the expense of the literal word, also known as Dynamic Equivalence. So, which translation is right for you? Well it depends! For an in-depth study of Scripture a translation on the Word for Word side of the spectrum would be ideal. If you are looking for a Bible for devotional use then a translation closer to the Thought for Thought side might suit your purposes. We are blessed to have a wide variety of English translations which are helpful for our growth as Christians. Having several translations available is always a good idea so you can compare words and thoughts to gain a better understanding of what God’s Word says.

No matter which translation you choose, it is always important to ask the Holy Spirit to open your eyes to see and heart to comprehend God's Living Word. |

AuthorPastor J-M shares some occasional thoughts and musings on our life together as followers of Christ. The views are his own. Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

- Home

- About

-

Learning & Growing

-

Sermons

>

- 1 Samuel

- Lent

- Spiritual Conversation

- Advent

- 1 Timothy

- Single Messages

-

Older Sermons

>

- Judges

- Joshua

- Galatians

- Lamentations

- 1 Peter: Living Hope

- Acts

- What Does This Mean?

- Gospel Identity: Gospel Living

- Nehemiah

- Questions of Faith

- Proverbs

- Hebrews

- Sermon on the Mount

- 1 Thessalonians

- Psalm 23: Walking with the Lord

- I Believe: The Apostles' Creed and a Living Faith

- 1 Corinthians

- Difficult Questions

- Genesis: God's Endless Faithfulness

- The Lord's Prayer

- Mark

- Genesis

- Bible Studies >

- Kids

- Blog

-

Sermons

>

- Worship Videos & Resources

- Contact

- Home

- About

-

Learning & Growing

-

Sermons

>

- 1 Samuel

- Lent

- Spiritual Conversation

- Advent

- 1 Timothy

- Single Messages

-

Older Sermons

>

- Judges

- Joshua

- Galatians

- Lamentations

- 1 Peter: Living Hope

- Acts

- What Does This Mean?

- Gospel Identity: Gospel Living

- Nehemiah

- Questions of Faith

- Proverbs

- Hebrews

- Sermon on the Mount

- 1 Thessalonians

- Psalm 23: Walking with the Lord

- I Believe: The Apostles' Creed and a Living Faith

- 1 Corinthians

- Difficult Questions

- Genesis: God's Endless Faithfulness

- The Lord's Prayer

- Mark

- Genesis

- Bible Studies >

- Kids

- Blog

-

Sermons

>

- Worship Videos & Resources

- Contact

RSS Feed

RSS Feed